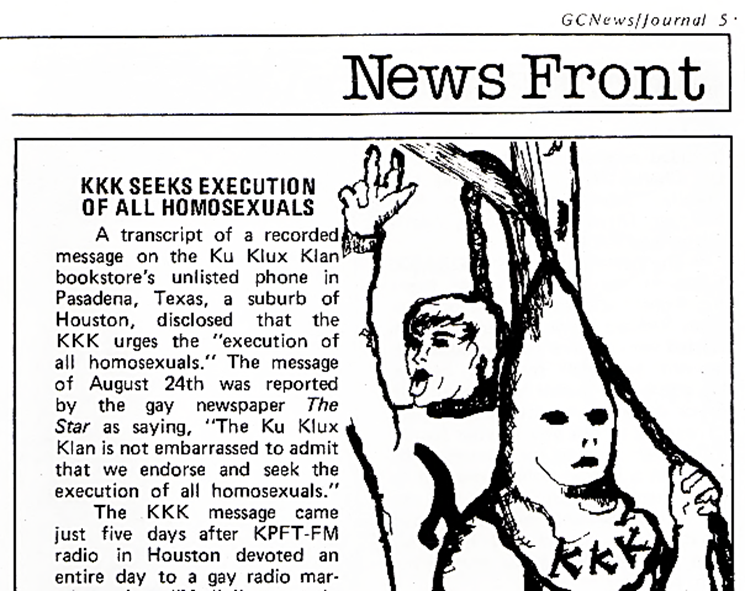

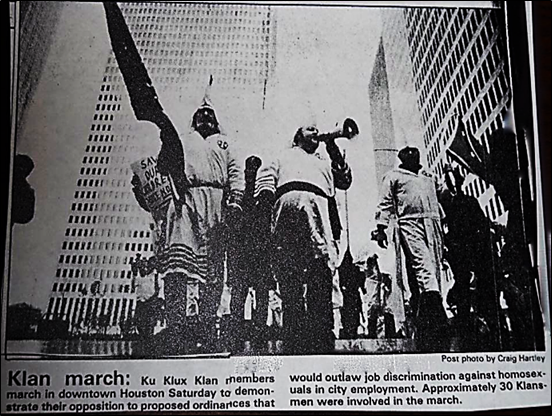

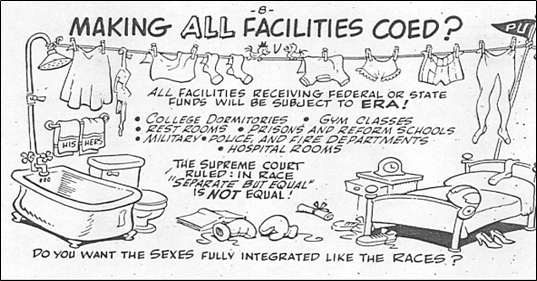

From what I can tell, my great-great-grandfather fled Mississippi to pass as white as his family was documented as being “Mulatto/Negro.” He taught his son, my white-passing great-grandfather to support the culture of Jim Crow, who, in turn, passed these trauma-based values onto his descendants. Consequently, I grew up two blocks from the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) headquarters in Pasadena, Texas, at a time when the KKK and local leadership teamed up to fight against LGBTQ+ equality. The KKK would pass out fliers with caricatures of non-heteronormative people, warning the public that people like me were dangerous. I remember the KKK marching in the streets carrying signs that instructed the adults around me to “frag a fag” in order to “save our children.” I also remember when a popular Houston mayoral candidate, Louie Welch said that the best way to address the HIV epidemic would be to “shoot the queers.”

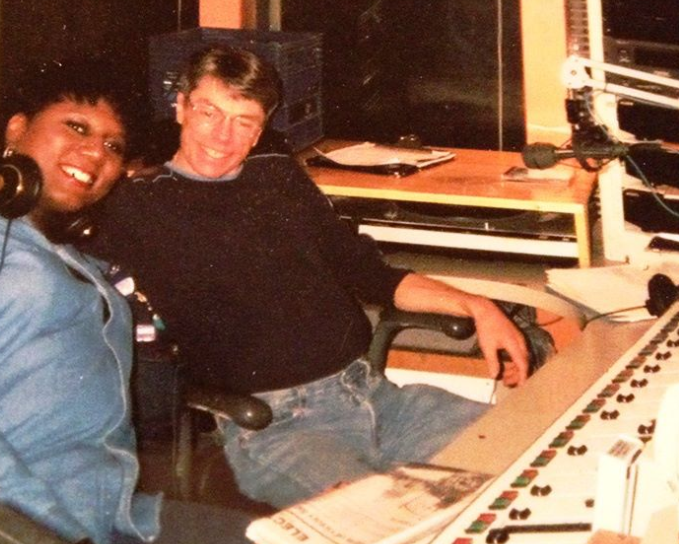

In the 1980s, a gay friend of mine took me to Houston’s bar scene and introduced me to a few trans people, though I was unable to find the sort of community support I needed. Being out at that time, without community, was incredibly difficult; I was beaten, harassed, and expelled from high school because my mere presence was deemed to be a “distraction.” Under such pressure, I went back into the closet and attempted to pass a cishet guy. After a few years of being closeted, I was making preparations for suicide. However, one night I found a radio show from Houston’s KPFT called After Hours. It’s worth noting that the KKK had bombed KPFT. Twice.

Jimmy Carper hosted the show and his co-host, Sarah DePalma, would eventually wind up taking me to my first equality march in Austin. Sarah gave me the contact information for a local trans group and I sent them a letter to their PO Box. Serendipitously, I received a call back the same night I was writing out my suicide note. That night, Houston’s trans community saved my life.

Having found community, I was able to come out, again, in the 1990s. However, the price our cishet-supremacist society made me pay for not being cisgender was that I immediately lost my job, my family, and became homeless during a time when being cisgender was required to access social services.

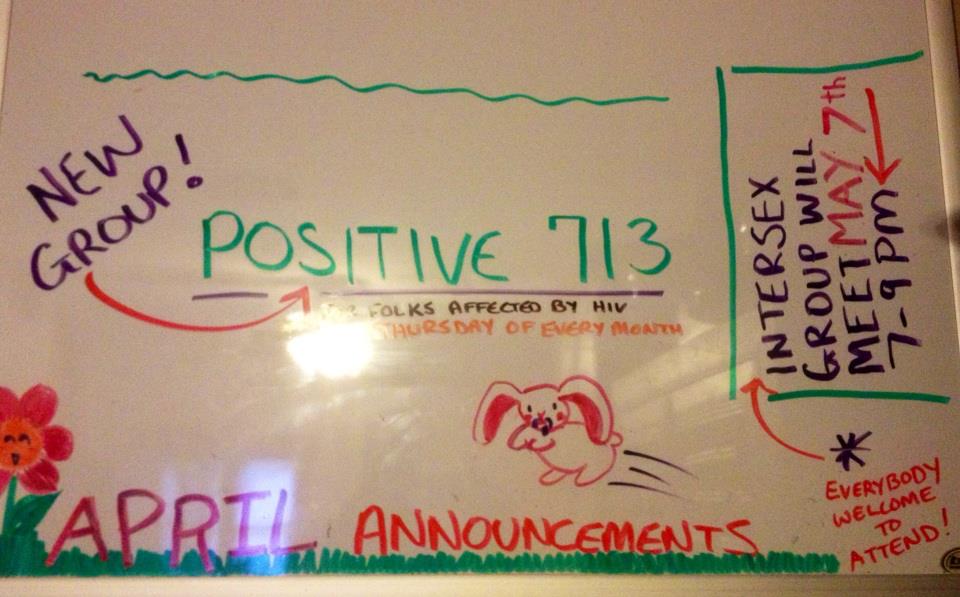

However, I and a small group of non-cisgender people formed something of a collective in a terribly run-down trailer and it was in that space that we formed a non-profit organization that would go on to provide housing, social services, peer support, and even medical care for the gender-expansive population.

My great-great-grandfather was faced with a choice that would affect the rest of his life: would he be truthful about his ancestry and confront the oppression such a truth would bring, or would he hide his ancestry and try to pass for a white man. He chose to live a closeted life regarding his race and, whether intentional or not, perpetuated the very culture he himself attempted to escape. I, like him, had something of a similar choice: would I be truthful about my gender, or would I hide it and try to pass as cisgender? I, like my great-great-grandfather, faced a social foe that was firmly rooted in the same toxic culture.

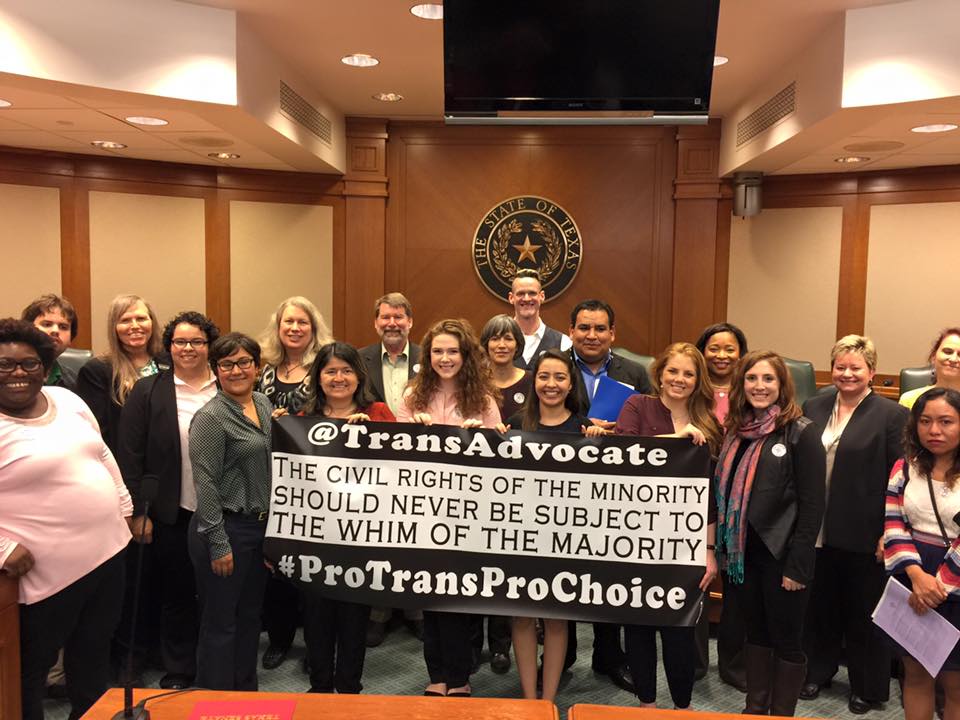

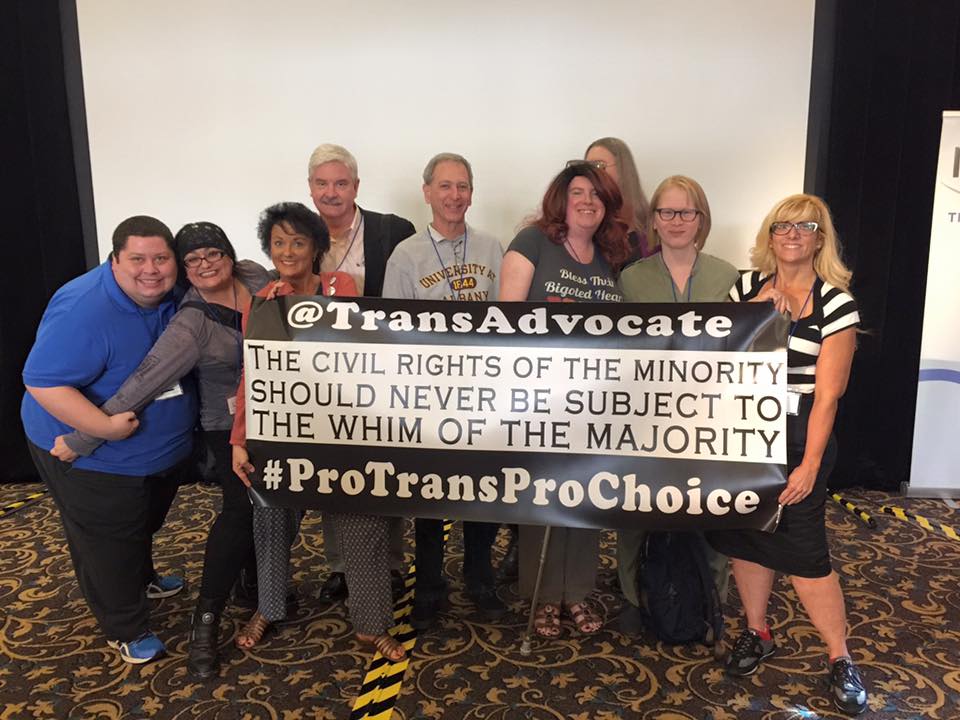

Indeed, I see the forces that shaped both my family and my experience as a queer trans woman in the current panic about Black Lives Matter, Critical Race Theory, abortion care, body autonomy, and transgender existence in our society today. While I am proud that I made a different choice than my great-great-grandfather, an empowered community was key and that wasn’t something that existed for my ancestor. For that reason, I am dedicated to the work of overcoming the material and psychosocial trauma of systemic oppression.

I feel incredibly grateful that I have been able to spend a quarter-century cultivating, maintaining, and expanding resources for the gender-expansive population. The practical consequence of my lived experience as a survivor of generational trauma, a queer trans woman of the South, and an activist who, with the help of my fellow community members, organized much with very little, is that the work of social justice is either intersectional or it isn’t just.

I was mentored under the queer Southern stewardship of the likes of Ray Hill, Phillis Frye, and Monica Roberts. Cultivating unity rooted in a shared mission generates the meaning and purpose necessary to endure the marathon work of social justice. It is meaning that sustains people and purpose that nurtures community, drives innovation, and focuses attention on what is truly important: community empowerment. It’s literally why I’m here.